In war torn Berlin, the city relies on a mix of grizzled veterans of hundreds of fires and inexperienced kids fresh from training. This is the story of a single station on a single night as bombs fall and fires burn.

As darkness descended upon the city, I made my way towards the fire station. It was an imposing three story stone building a few blocks west of the Tiergarten. Had it not been for three massive red doors, it could have been an apartment or office building. Rows of windows on the second and third floors faced the street. They glowed slightly in the fading light of the sun. I stood for a moment and took in the building before I knocked on the middle door.

It took a few minutes and three knocks, but eventually the door began to raise with a creaking noise. I found myself staring at the cab of a green Mercedes fire engine. Footsteps echoed on the concrete floor and a firefighter appeared from behind the engine.

“You must be the journalist,” he said, making the word journalist sound a touch profane. I replied in the affirmative and he said, “Name’s Frei. I drive the ladder truck.”

My eyes followed the direction of the thumb he used to point towards a shiny green truck with a turntable ladder.

“Oberwachtmeister Weber is upstairs,” Frei said, “Follow me.”

We walked across the apparatus floor. The station smelled of smoke, mold, sweat, and diesel exhaust. Four brass poles along the far wall ascend upwards and disappeared into the floor above. The stairway in the back of the station rose so steeply that, for a moment, I felt as if I were climbing the Swiss Alps. The second floor consisted mainly of one large room with iron cots along both walls. A few sparse decorations hung on the walls, mostly pin-up girls and a few official posters. One was of a grinning skeleton hurling a bomb earthward. Large block letters proclaimed “The enemy sees your light! Blackout!” The cots were all made up in regulation military fashion with the sheets and blankets folded with precision. A large picture of Saint Florian, the patron saint of firefighters the world over hung next to the fire poles.

“The washroom’s over there,” Frei said as he indicated a hallway. “So’s the kitchen. Or what passes for one. Our water pressure isn’t great these days.”

We found Obermachtmeister Karl Weber sitting behind a cluttered desk in a small office just off the main room. The stirring sound of a military march drifted from a radio atop a metal file cabinet in the corner. He stood to shake my hand, insisting I call him Karl as he motioned me to sit.

“So,” he said as he lit a cigarette, “You are writing a story about the fire brigade. Why?”

I gave him my rehearsed response about wanting to showcase the heroism of those who labor under the bombs, attempting to save lives. Karl silenced me with a wave of the hand.

“We’re not heroes,” he said as he exhaled a cloud of blue smoke which formed a halo over his head, “We’re firemen.”

The war weighs heavily on Obermachtmeister Karl Weber, station commander. “We’re not heroes,” he said, “We are firemen.”

+++

Karl Weber is a man of medium height and the build of a middleweight boxer a few years past his prime. His brown eyes, with dark bags underneath, managed to look both amused and exhausted at the same time. Permanent creases line the corners of his mouth. A few flecks of gray around the temple made him look older than his thirty-three years. Karl grew up in the Charlottenburg part of Berlin, not too far from the fire station he now runs. From an early age, he found himself drawn to the fire service, more from the excitement and the nice uniform than anything else. In 1929 at the age of 19, he joined the Berlin Fire Brigade as an apprentice fireman.

In 1935, Karl enlisted in the army as a reservist. He has seen action in Poland, Belgium, France, and Russia. It was in the frozen hell of Stalingrad that a few pieces of shrapnel buried themselves deep into his hip, thigh, and knee. Doctors removed most of it, but the remaining shards of metal cause him to walk with a slight limp. After a long, difficult recover, Karl received a discharge from the Army and orders to return to Berlin, where a new war was being waged.

+++

After a few minutes of small talk, Karl and I walked out to the main room and joined the others around a table. A stack of magazines under one table leg kept it steady. I’d met Frei earlier. The other two, Baumann and Fischer, nodded as Karl made introductions. They eyed me warily as I sat across from them.

Just a few short years ago, in the relative calm before the war, this station had twelve men assigned to it, six per truck. Now they make due during the daytime with only two per vehicle. At night, the professional firefighters are joined by teenage auxiliaries, young men and women eager to do their bit for the war. Hastily trained and working under the guidance of experienced old hands like Karl, these youthful volunteers make up the frontline defenders of the citizens of Berlin.

“We’ve only just got our volunteers,” Karl said. “They haven’t really gone through a big raid yet, at least not as firefighters.”

“What is it like?” I asked. “Putting out fires in the middle of a raid.”

“Oh, it’s not so bad,” Karl replied. “If it’s a big enough fire, you don’t notice the bombs.”

We were interrupted by the sound of footsteps and laughter on the stairs. Four young men in ill fitting uniforms walked into the room. They carried their helmets tucked under their arms and had their gas mask cases slung over their shoulders. Four young women in baggy blue-gray coveralls followed them in. Karl gave them a few curt orders to put their gear on their assigned trucks and to start polishing the engines.

“Just because we are war doesn’t mean we go around looking like some voluntary fire brigade from the countryside,” Karl said. This is Berlin. A well polished engine indicates a well polished crew.”

I asked permission to follow the volunteers downstairs and Karl nodded his approval.

+++

Monika Schneider is a quiet, serious young woman of 17. She wears her long blonde hair in pig tails and regards the world with bright blue eyes. Her gaze penetrates you as if she is searching your soul, probing from your hidden fears and weaknesses. With increasingly large numbers of young women being drafted into war related occupations, Monika had a choice of either training to operate an 88mm antiaircraft battery or the fire service.

Young women like Monika Schneider (right) have stepped forward to serve on the front lines of the air way. Their job? Save lives.

“My older brother Gunter flew a Heinkel,” she explains as she wipes polish off the engine in a circular motion. “He was shot down and killed during a raid on London. I didn’t think I could bring myself to shoot down some English girl’s brother. So I chose the fire brigade.”

After a two week course in which she and her fellow auxiliaries drilled on donning their gas masks until they could do it in their sleep, navigated obstacle courses to hone their agility, and lectures on the various types of bombs employed by the enemy, the were deemed ready for assignment. Their only experience with an actual fire came when they were allowed to spray water on a burning haystack. But there would be plenty more fires to come.

+++

In some ways, Fritz Kluge is a poster child for the new Germany. Born into a working class family near the center of the city, Fritz joined the Hitler Youth at age 10. He’s fifteen now, and has also had enough training to qualify him to help the fire brigade and to wear the coveted HJ firefighting patch on the sleeve of his coat. Fritz has a ready grin, which tends to be a bit on the cheeky side. I listen as he trades barbs with some of the other boys. If they were at all nervous about the possibility of a raid that night, they did not show it.

Two young volunteers from Karl’s station operate at a fire in Charlottenburg.

+++

“Fliegeralarm!”

A sudden shout which came to us via the hole from which the fire pole descended broke the silence. The youths glanced up from their work, eyes darting back and forth. A minute later Karl came down the stairs and said “Listen up, the formation we’ve been tracking has passed east of Hanover. We are probably the target for tonight. Apparently it is a heavy raid.”

The young people nodded, their expressions serious.

“Gather up flashlights and place some onto the truck and then bring the others into our shelter,” Karl said. He gave orders with the rapidity of a machine gun. “Gather up some buckets of sand from the closet and put them near the station doors. Bring your helmets and masks into the shelter with you. And you need to visit the lavatory. Void your bladder and bowels if you can. Should you get struck with a shell splinter in the guts tonight, it’s best to not have anything inside them that can cause an infection.”

The young people scattered in eight different directions to begin work on their assigned tasks. Karl handed me a metal container with a gas mask inside, identical to the ones carried by the firefighters, and also a steel helmet. The helmet looked similar to a Germany Army helmet, but it had the addition of a leather flap attached to the back of it and a reflective stripe painted around it.

“That flap keeps embers from blowing under your collar,” Karl said. “Hurts like hell when that happens.”

I asked if there was anything I could do to help and he said no.

“You’ll only be in the way. Just wait until it is time to go into the shelter.”

I stood along the back wall and watched the young volunteers as they scurried back and forth carrying out their instructions. The older men moved more slowly. For them, the impending raid did not represent excitement, but rather one more thing for them do; one more challenge to face. Their faces bore the looks of men who have seen so much of the depths of the evil that men do that it no longer registered in their minds. They walked with shoulders slumped forward as if the weight of their job keeping the citizens of a city under aerial siege safe pressed down on them.

The tasks completed, we walked down a dark, narrow hallway until we reached a solid oak door. Karl pushed it open with his shoulder and ushered us inside. It was a small, sparse room. Ten chairs, five along each wall, provided the only place to sit. A telephone and a radio occupied a table in one corner and a large, detailed map of the city filled the wall above it. I took a chair and settled in to wait.

+++

An air raid is a singularly terrifying experience. You sit in near darkness and listen to the shriek of bombs and the thundering blasts of anti-aircraft guns. The building sways when a bomb lands nearby and dust floats down from the ceiling. As your mind envisions every form of fiery death that could happen, you try to think of something, anything, to keep you sane. You grab onto the first pleasant memory you can conjure up the way a drowning man grasps at a life jacket. Your heart pounds almost audibly in your chest as your breath comes in ragged gasps as if a tight band constricted your chest and kept your lungs from fully expanding. That’s an air raid.

Those around me took the raid in stride. When the flak batteries atop the Zoo Tower a few blocks away opened up, one of the Hitler Youth boys said “I guess they’ll teach the Tommies a thing or two.” Karl leaned his head back until it rested against the wall and closed his eyes. Frei smoked a cigarette. Baumann and Fischer played cards. The auxiliaries sat on the edge of their chairs, ready to spring into action with all the enthusiasm of youth.

“So how do you know if you get an assignment?” I asked.

“The phone rings,” Karl said without opening his eyes, “Or if the phone system goes down, they send a messenger by on a bicycle. He knows where to find us back here.”

The sound of aircraft engines penetrated the brick walls of our shelter. Frei looked up for a minute, a quizzical look on his face. After a moment he said “They aren’t dropping over the city center. Looks like Charlottenburg is going to get it tonight.”

Fischer grunted, “Too bad they didn’t drop it on Wedding. Might bump off a few kozis that way.”

I lost track of how much time we were in the shelter. It could have been thirty minutes, but it seemed like thirty hours. Finally the phone rang. Frei grabbed it and said “Fire station” by way of greeting. He scribbled something on a scrap of paper and hung up.

“Where?” Karl asked, his eyes still closed.

“They said just drive west towards the fires,” Frei said.

The morning sun revealed a landscape of utter devastation.

+++

A few minutes later we pulled out of the station. I sat in the cab, squeezed in between Baumann and Karl. The boys rode the ladder truck and the young women traveled on the engine, but they had to stand onto the tailboard and cling to a metal bar. We operated with no lights, and the going was very slow, though we could see fires burning in the distance. Searchlights stabbed at the sky like accusing fingers. Occasionally, we caught the glimpse of a bomber. But mostly we kept our eyes focused on our destination.

“Are you having fun yet?” Karl yelled over the sound of the planes, bombs, and our own engine.

I thought it best not to answer. I looked over my shoulder and barely made out the faces of the four young women; Monika, Elisabeth, Ingrid, and Lotte. I thought I might see fear, but instead I saw excitement mingled with determination in their young eyes.

“Stay near the truck when we get there,” Karl said, “And be careful, there will probably be a gap of about thirty minutes where it will look like the raids over, then they’ll come back to try and catch us in the open.”

Which is exactly where we will be, I thought. When we reached our assigned sector, the heat slapped at my face like an oven. Baumann stopped the engine and the crew threw themselves into their duties with a vengeance. Monika and Elisabeth grabbed a thick hose and dragged it towards a fire hydrant while Ingrid and Lotte uncoiled another section and stretched it towards an apartment building. Flames showed in the windows of the top two floors.

I heard a grinding noise and turned to see the ladder from Frei’s truck extend upwards towards the roof of the building. Fritz and another young man scrambled up as the ladder moved. I looked around for Karl, but did not see him. A minute later, he emerged from the building, pausing for a moment in the doorway as smoke curled around him. It almost looked as though the smoke were wings and he were an angel.

“They’re dead,” he yelled to Baumann. “Let’s go ahead and see if we can knock this fire down and move up the street a bit.”

+++

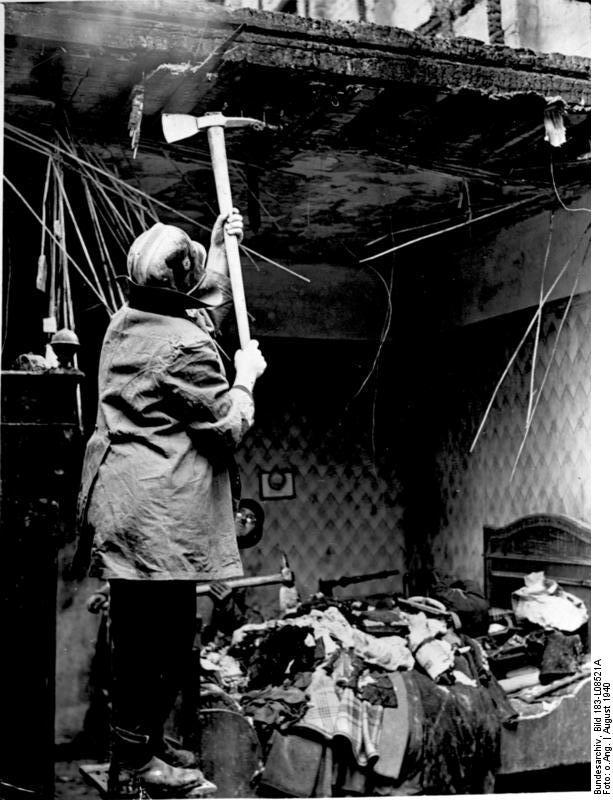

For the next few hours, I was treated to the sight of Karl and his crew of veterans and kids alike tackle one blaze after another. I learned that he was right. I found myself so fixated on the fires that I no longer heard the bombs. While a blessing, it nearly proved fatal. At one point, Karl froze and looked up for a second, then he screamed at us to get down. I hit the pavement as fast as I could manage. The explosion lifted me up and then shoved me back into the ground with enough force to empty my lungs of oxygen. It took a few minutes for my ears to stop ringing and my breath to return. When it did, I looked up and saw Karl smiling down at me.

“Bit more than you bargained for, eh?” he asked.

I stood with as much dignity as I could muster and busied myself by brushing dirt off my clothes. It is difficult to describe everything I witnessed this night, as scene ran into scene. I watched these young men and women perform feats of incredible bravery with the skill of seasoned professionals. Every now and then, one of them would flash me a grin from a soot lined face, or give me a nod of assurance. I had to remind myself that had the world not gone mad, they might playing games in the street, or complaining over their amount of work their teachers had given them that day. But here they were, performing a job usually reserved for grown men. But I can’t help but ask myself, at what cost? What will their lives be like when all this is over? Will they ever be able to forget what they’ve seen?

+++

A few hours after daylight and seven hours after the phone rang at the fire station, we were permitted to return to the station for a two hour period of rest. We stank of sweat, phosphorus, cordite, and smoke. Our lungs were raw. My skin felt sunburned, owing to the intensity with which the fires burned. When we arrived at the station, no one had the energy to walk upstairs to the bunkroom. We collapsed on the floor or on one of the trucks and let exhaustion carry us away. I felt as if I had just closed my eyes when Karl slapped my shoulder and said “Come on. Back to work.”

Fritz (right) grabs some rest in between alarms.

Our new assignment was to check shelters for victims, living or dead. I was allowed to put on my gas mask and accompany them into the buildings as we searched below ground level for any survivors. As we entered one large basement, our flashlight beams caught the faces of people sleeping as they sat on two wooden benches along the wall. I wondered why they didn’t wake up and asked Karl if we should shake them or pat them on the shoulder.

“Look at the faces,” Karl said, “See how they have a bit of red in their cheeks? They are dead. Carbon monoxide poisoning. It happens when the fire burning above them uses up all the available oxygen. They are the lucky ones. They just fall asleep. Far better than burning alive.”

As we walked up the stairs and out the doorway, Karl removed a piece of chalk from his pocket. His hand shook slightly as he scrawled “20 tot” on the brick façade near the door.

“Come on,” he said to me, “We’ve got two more blocks to go.”

This is a work of fiction. I wrote this piece as if a journalist did a feature on the fire station where the characters in my novel work. If a reporter spent a night with them, it might have happened this way.

Well done. This piece had the feel of people trying to do their job in the midst of a war. Many vivid moments in the piece really give it life.

LikeLike

Thank you. Had I not become a firefighter, I wanted to be a journalist (print, not television).

LikeLike