Dear Readers,

If you were to poll a random cross sections of Americans and ask them what professional sport was the most popular in the nation prior to the shotgun marriage of television and football, I’d bet dollars to donuts that the respondents would answer “baseball” without hesitation, mental reservation or secret evasion of mind. While it is certainly true that the Overlords of the Outfield did indeed hold sway over the imaginations of the public in the post-war era, it is not the whole truth. By that, of course, I refer to the second great cataclysm to strike the world following close on the heels of the War to End All Wars. Before said war it was not the Bandits of the Bullpen who most captured the hearts and minds of the American people, but rather the Rajahs of the Ring. Yes, Dear Readers, I refer to the sport of boxing.

La dulce ciencia is perhaps the oldest sport known to man, a fighting companion, perhaps, to the oldest profession. No doubt cavemen engaged in fisticuffs as readily as some men do today. The Book of Genesis tells us how Cain slew Able, but it leaves out the method with which Able was dispatched. Given the fact that they were the third and fourth humans, respectively, one can only assume Cain slew his brother with his bare hands. The Good Book details frequent battles between opposing groups, often resulting in the vanquished being “smote hip and thigh”, whatever the hell that means. No less an authority than Homer, the blind bard of antiquity, spoke of the innate desire of one man to smash his face into the fist of another. Odysseus, of whom Homer sang praises, settled things with his fists when the need arose. Indeed, the Pantheon of Boxiana reads like a who’s who of famous writers. Hemingway, who spent time in the ring, Jack London, Joyce Carol Oates, and the great A.J. Liebling, all devoted time to chronicle the Sweet Science of Bruising in a manner worthy of Shakespeare. The question we must ask is why? What drew literary heavyweights to wax poetic (and sometimes wane) about their counterparts in the ring? Just how popular was the fight game in the past? Well, Dear Readers, I shall attempt to answer my own questions.

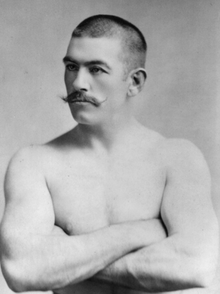

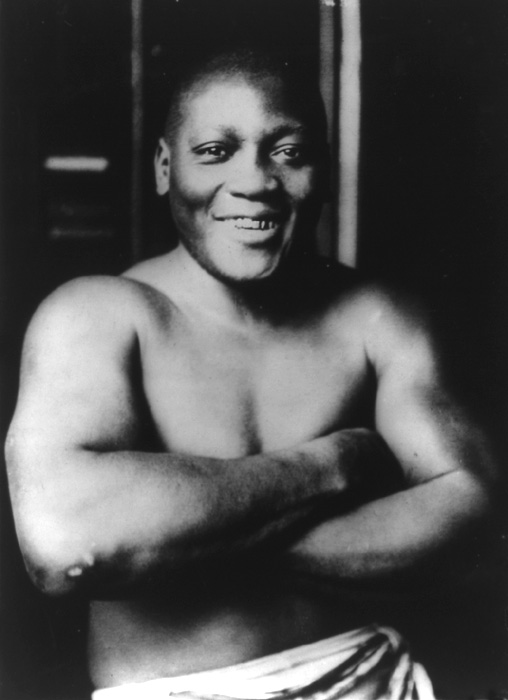

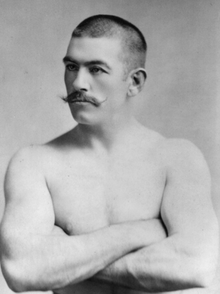

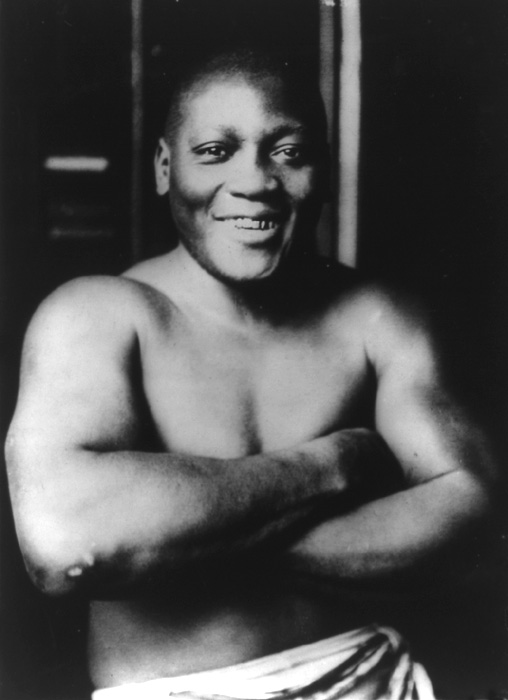

We need not venture all the way back to the 19th Century to explain the rise of pugilistic parade of boxers turned celebrities, though the Boston Strong Boy might take issue with such a dismissal. No, we should first turn our eyes to the island city of Galveston, which gave birth to the first superstar black athlete, who is a worth early example of the impact of a sport on our society. It took some doing, but eventually Jack Johnson, the Galveston Giant, convinced Tommy Burns to schedule a title fight. Burns had, earlier, defeated then champion James Jeffries. Burns and Johnson touched gloves in Australia in 1907. Fourteen rounds later, Burns was on the mat and Johnson was the champion. That a black man had beaten a white champion shocked the world, no matter how skilled said black boxer was.

This set off a desperate search for a “Great White Hope”. White American fans of the fight game couldn’t stomach a black champion. Surely someone, anyone, could come forward and wrest the title from Johnson’s massive fists. A hope, both likely and unlikely, stepped forward. James Jeffries said he’d give it go, although he had thrown nary a punch in six years. The combatants met in Reno, Nevada. Johnson knocked Jeffries down twice before his corner threw in the towel to prevent him from having a knockout on his record. Jack London, sitting ringside to cover the bout, summed it up succinctly. “Once again Johnson has sent down to defeat the chosen representative of the white race, and this time, the greatest of them all.” The country reacted with shock, nay, horror!

What may have seemed like a simple boxing match was anything but. Riots swept across the United States, with dissatisfied white men storming black communities to set homes and businesses on fire. Some estimates state that around twenty-five people died and a few hundred more injured. Consider the significance, Dear Reader. Have we ever seen nationwide riots after the Patriots win (another) Super Bowl? To my knowledge, the Johnson v. Jeffries prizefight is the only sporting event in the United States to ever touch off nationwide rioting due to the outcome. But alas, Dear Reader that is exactly what happened when Johnson won.

The saga of the Galveston Giant is a great one, but time and space prohibit me from giving it anything more than a light jab on the chin. Eventually, the world found its Great White Hope. In a fight scheduled for 45 rounds, Jess Willard sent Johnson to the canvas in the 26th. Boxing reigned supreme in the 1920s. No less an authority than A.J. Liebling, the Heroditus of the Prize Ring, noted that during a decade known for flappers and prohibition, Jack Dempsey got more headlines than Babe Ruth. And made more money too. It would take over twenty years for another black boxer to challenge the established order of the sports world at the time, but when he did so, he’d do it with, at least on the surface, the support of white America.

When Joe Louis, the Brown Bomber, stepped into the ring on June 22, 1938, he not only carried his own desire to avenge his earlier defeat to Max Schmeling, he also carried the hopes and best wishes of the United States. A couple of weeks before the fight, no less a person than Franklin Delano Roosevelt met with him and gave him sincere wishes for success. Schmeling likewise sallied forth to do battle with the hopes of a nation upon his broad shoulders. A second victory over Louis would be a propaganda coup for Hitler, who could point to it as an example of Aryan supremacy. The media cast this titanic battle as one between Democracy and Fascism, the Brown Bomber and Hitler’s man! Such makes for good copy, but the truth was that Schmeling was not an admirer of Adolf. The manner in which this fight was covered meant that, for the first time, white Americans felt comfortable cheering for a black boxer, even if they would not have wanted him to live next door or marry their daughter.

On that fateful night, the men eyed each other from across the ring whilst millions tuned in around the world to hear the call. 70,000 lucky fans were able to watch what promised to be an epic battle between two noted pugilists. Some estimates have as many as 70 million Americans listening at home on their radios. What makes this shocking is that the population of the United States was around 129 million. That, Dear Readers, is over half of the country. Consider this, even the most watched Super Bowls don’t bring in that percentage. Around the world, people tuned in on shortwave radios as well to hear it live. If people hoped for a long fight, they would be disappointed. Louis dispatched Schmeling in just over two minutes. Had you been at home on this fateful night, you’d have heard the broadcaster say “Schmeling is down……the count is five!” This became one of the most recognizable radio calls for many years to come, indeed, among fans of the sweet science, it is known even to this day.

These are but a few examples of the hold la dulce ciencia had over the American public those many years ago. There are many reasons for boxing’s decline following the super bouts of the 1980s. But for those, like myself, who are fans of the sweet science of bruising, we can look back on a time in which the pugilistic art bouth captivated and repelled us, a time in which in divided us and brought us together, and a time in which it showed both racial division and unity. Some learned historians have called the 20th Century the American Century. If this is true, than at least during the first half, boxing was America’s Sport. Alas, the sport has fallen a mighty long way since June of 1938. It may well never recover.

But among the hardy few pugilists who trade jabs in the ring today, one constant has remained the same since bareknuckle brawler John L. Sullivan plied his trade. Boxing has always been a working class and/or immigrant sport. My own ethnic group, the Irish, became the first great bareknuckle champs in the United States. We gravitated towards the prize ring, perhaps due to the fact that we discovered a way to get paid for something we did for free on a typical weekend. In the 20th Century, we saw black fighters, Jewish fighters, and Italian fighters like the great Rocky Marciano. Today, the Hispanic community has strong ties to ring. While a Mexican-American kid laces up his gloves for the first time today, he or she is following a path blazed by other immigrants who, though they might have had a different shade of skin or language, shared the desire to fight their way to the top of a very difficult world.

I will leave you with this thought. One cannot separate the history of a sport from the history of a country. The two are as entwined as two lovers in a bed. To understand one, you must understand the other. To those who opine that in the grand scheme of things, sports are irrelevant, I only ask them to consider those killed in the riots following Johnson’s victory. Tell those murdered by mobs angered over the outcome of the bout that sports don’t matter. For those poor souls, the sport was life or death.

Don’t drop your guard and remember to stick and move.

Hutch