(For my usual readers, this post is being done as an assignment in one of my PhD courses, so it is not the standard fare.)

The three generations before me, my father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all steelworkers. Had the American steel industry not collapsed in the decade I was born (1970s), I would have no doubt followed in their footsteps. Although I am not doing my seminar paper in this course on the steel industry, I decided, for this assignment, to look specifically at the state of American steel production at the end of the 19th Century, when the United States was in the process of becoming a major producer of steel. Of course, if the topic I selected goes down in flames, like the American steel industry did, I might switch over to steel as the topic of my final paper!

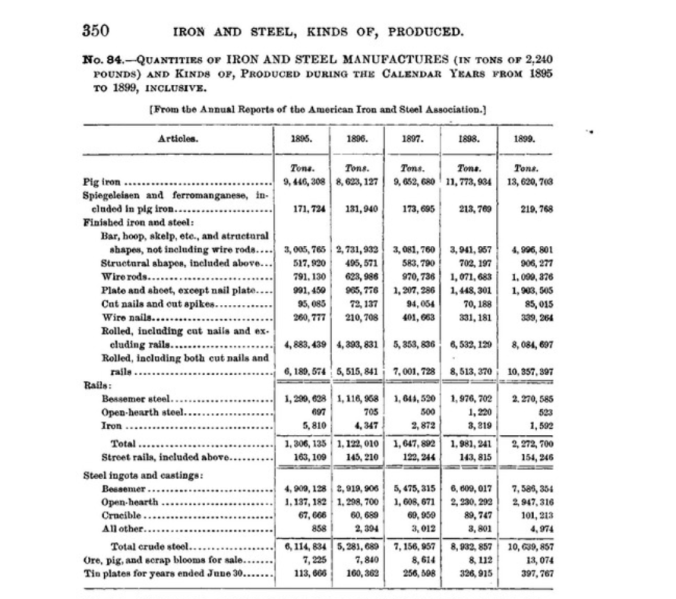

The dataset I looked at for this assignment is from the 23rd Statistical Abstract of the United States published in 1900. It contains a chart (included below), which illustrates the quantities and tonnage of iron and steel produced in the United States between 1895 and 1899 as reported by the American Iron and Steel Association. The chart has some interesting bits in it, from which, I think, we can draw a picture of what the country looked like and was experiencing during those four years from an economic standpoint. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/statistical-abstract-united-states-66/1900-21993?page=367

First of all, most of the tonnage produced at the time was pig iron. I am familiar with what this is, since I grew up hearing the term used frequently by my father and grandfather. When I was little, I thought it had something to do with pigs. It doesn’t. Basically, pig iron is heated in a blast furnace until it is sort of a molten liquid form, then transferred to a steel mill to be refined into actual steel. In other words, you need pig iron to produce the steel. As you can see from this dataset, the total tonnage of pig iron exceeds that of any other single item produced during all five of these years, but the total tonnage of all of the products produced exceeds the tonnage of pig iron. This would indicate that the pig iron produced in a year wasn’t necessarily being used to produce steel products in that same year, meaning steel production carried over from one year to another. One curious note is that pig iron production fell in 1896 and then increased again in 1897. The year 1899 shows a 35% increase in production over the base year of 1895.

Prior to really looking deeply at this dataset, I assumed, given that it was the late 19th Century, that the majority of steel production would have gone into making railroad ties. However, this dataset shows something different. The majority of steel was produced as rolled steel (used to make steel components of machinery) and steel ingot which is used in building construction. For a second dataset, I looked at immigration during this time period, to see if it was immigration driving the demand for steel to produce housing. The immigration report from the 23rd Statistical Abstract of the United States (1900) indicates that between 1895 and 1899, the United States absorbed 1.7 million immigrants. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/statistical-abstract-united-states-66/1900-21993?page=415

Immigration alone cannot account for the increase in steel production, or the mass production of building components. To use this as the simple explanation would be to attach the assumption that all immigrants were destined to live in buildings with steel frame construction. In his article “Statistical Models and Shoe Leather,” (1991), Freedman warns about the attachment of an assumption to data models which may then lead the investigator to build data around the assumption. In previous courses I have taken here, the need for solid empirical research was stressed by multiple faculty members. Keeping that in mind, when looking at these two datasets, I would state that the datasets prove two things empirically. One is that our steel production increased between 1895 and 1899, and that the majority of that steel was being used in either rolled steel or steel ingot. The second piece of empirical data is that immigration saw a modest increase during this same time period.

To take this study further and prove with solid empirical data that it was, in fact, immigration driving the boom in steel production, one would need to look specifically at immigrant housing. Where were these immigrants living? What construction records are there for buildings built during those same years and in the cities receiving the bulk of these immigrants. If such construction records exist, it might show that the boom in construction was actually in the realm of commercial properties, and thus totally unrelated to immigration. Conversely, it is possible that it was, in fact, residential structures driving the building boom, and thus the increase in steel production.

The use of raw data on things such as steel production, or immigration, is of use to historians as it can provide us with a basis with which to start our inquiries. It can even change the direction of our inquiries. As mentioned earlier, I incorrectly assumed that in the late 1890s, the railroads would be the largest consumer of steel. As it turns out, the builders were. Having lived through the collapse of the steel industry at the end of the 20th Century, and seeing my father lose his career, and my grandfather nearly lose his pension, it was bittersweet to look back at n era when American steel production was beginning to grow into the behemoth it would be by 1950. As the final piece of this post, we are to state what our major research topic will be this 8 week session. Pending instructor approval, of course, I will be examining the CB radio craze of the 1970s and early 1980s. I’m particularly interested in whether or not it was popular culture that created the CB craze, or if movies like Smoky and the Bandit, and songs like Convoy, reflected what was already happening in the country

BLH